Serial Killers are fundamentally uninteresting. They kill people, often in very similar ways, often a large amount of people. If you look up on Wikipedia a list of serial killers by the number of victims, you won’t recognise the names at the top of the list. Luis Gravito, Pedro López, Javed Iqbal, Mikhail Popkov. These people killed 50, 100, sometimes even 200 or up to 300 people. They killed children, girls and boys – they killed innocent men and women, often in incredibly debauched and horrible ways. Cutting them up, dissolving their bodies in acid, strangling them. Yet, we don’t know their names, and why should we? Serial Killers are boring. We should ignore their heinous crimes lest we bring them the fame and fulfilment they seek. However, serial killers still hold the public’s imagination in a unique way. It’s not because of their crimes – if it was, the names I have listed would be more recognisable. Instead, we are interested in stories, not the amount of people killed or how they died. ‘We tell ourselves stories in order to live,’ writes Joan Didion. It turns out we like to tell ourselves stories about death. Some stories stand out: Ted Bundy, Charles Manson, Ed Kemper. But one stands out most of all: Zodiac.

David Arthur Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen were on their first date on December 20th 1968, just a few days before Christmas. The couple met up with some friends, had dinner at a local restaurant and then drove along Lake Herman Road near the town of Benicia, California. Benicia had a population of around 7000, and was, for a brief thirteen months from 1853 California’s state capital. Faraday and Jensen stopped near a water pumping station at 10.15pm, presumably to kiss. At around 11.00pm their bodies were found riddled with bullet holes. Jensen was shot five times as she had tried to get away from the killer. About six months later Darlene Ferrin and Michael Mageau were attacked, just before midnight in their parked car, about six and a half kilometres from the Lake Herman site. Both were shot fives times with a 9mm Luger. The killer was then about to flee but heard Mageau’s moans and shot both victims twice more. About an hour after the murders, someone called Vallejo Police Department. Vallejo, California had a population of around 70,000 in 1970 and served as the state capital for less than a year before it was changed to Benicia. The man on the phone confessed to both the attacks on Ferrin and Mageau and the earlier murders of Faraday and Jensen. Ferrin died in hospital shortly afterwards. Mageau, miraculously, survived.

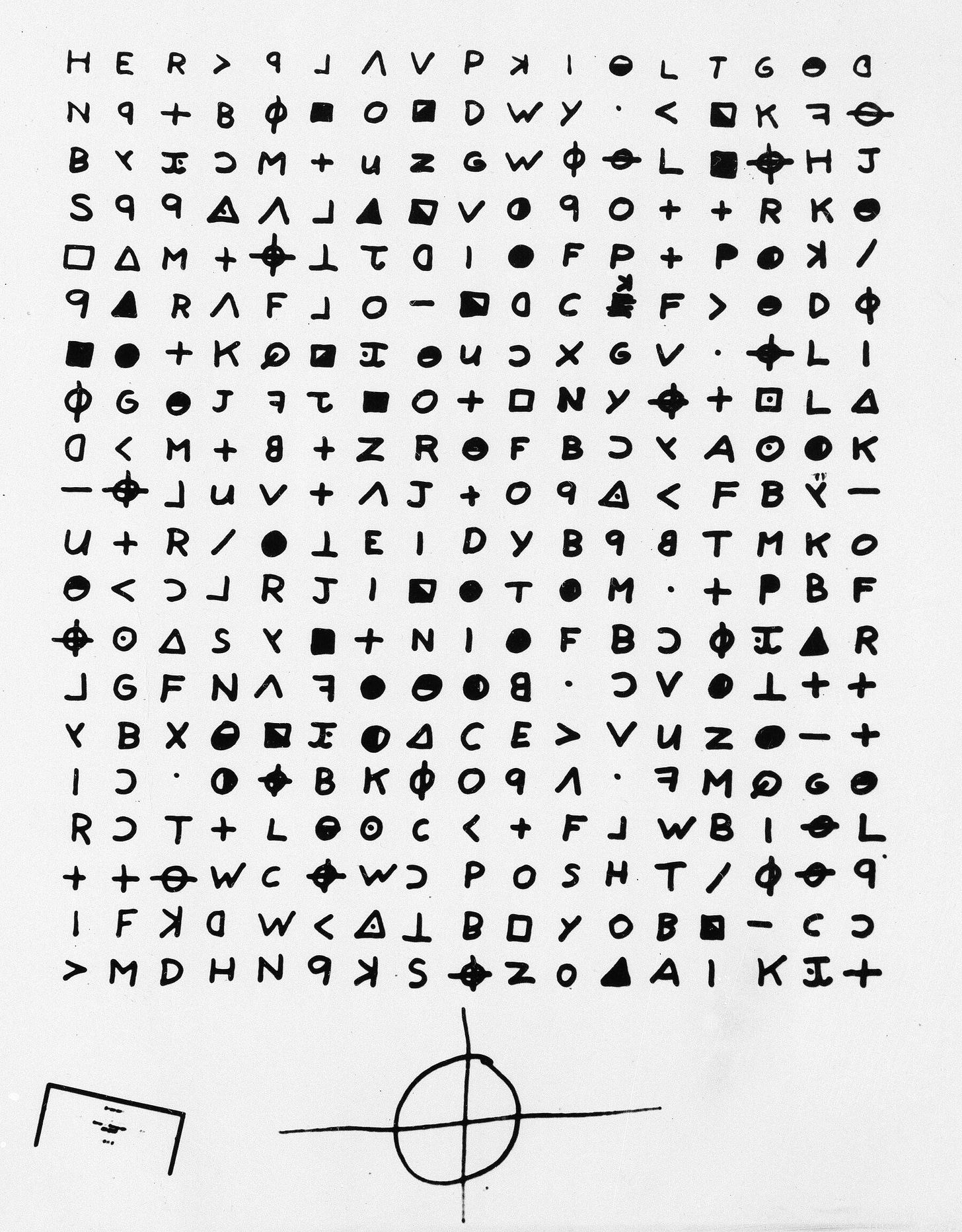

Then the letters started coming. Three of them at once, on August 1st 1969, to the major Bay Area newspapers: the Vallejo Times Herald, the San Francisco Chronicle and the San Francisco Examiner. The letters were almost identical in content but contained three separate parts of a cipher. The letters described the Lake Herman and Vallejo murders in detail. The cryptograms, solved by amateur sleuths, talked about ‘collecting… slaves’ for the ‘afterlife.’ Less than a week later came another letter to the Examiner. It opened with, ‘This is the Zodiac speaking.’ Thus, the legend was born.

You may know the rest of the story, or you may not. David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) tells it better than I could. More letters start coming, and more murders. A young couple was attacked at Lake Berryessa in September 1969, with the woman, Cecelia Ann Shepard, succumbing to her wounds. Here the Zodiac attacked in broad daylight, wearing a hood, and used a knife. The final confirmed Zodiac victim, Paul Stine, a San Francisco taxi driver, was shot by the killer in his cab. Zodiac took a part of Stine’s blood-soaked shirt. All this was seen by three teenagers who quickly reported it to the police. The suspect was a white male with short hair and of medium height. However, the police dispatchers – in a mix-up never explained – told officers to look for a black suspect. It is highly likely that officers passed the Zodiac as he was fleeing, without noticing it. Zodiac was within grasp, but he slipped away. More letters kept coming. Zodiac panic was in the air. He sent bomb threats and admitted to murders that he likely didn’t commit. Then it stopped. A letter came in 1974 – probably authentic. A few more came afterward – probably not. The Zodiac got away. He was never found. That’s why he continues to haunt our imaginations. He killed five people, with a gun or with a knife. But letters, the mystery, the branding, that’s what keeps the Zodiac myth alive.

But perhaps the Zodiac mystery has finally be cracked, at least according the novelist Jarett Kobek. Kobek did not want to write about the Zodiac, but somehow he’s written two books about him, published simultaneously: Motor Spirit and How to Find Zodiac. In Motor Spirit Kobek dives deep into hippie-era San Francisco, America’s revolutionary city. Suddenly the Zodiac doesn’t seem so abnormal or out of place. Late 60s San Francisco was a city on fire. Zodiac was in many ways the least of their problems. Kobek describes murders that make the Zodiac seem sane. Hippies committing acts of utter depravity under the influence of drugs. New, horrible crimes every day. ‘A wave of drug-induced violence starts around 1966 and won’t end until the 1990s,’ Kobek writes.

One of these acts of violence is the murder of Ann Jiminez. On the day that Zodiac killed at Lake Berryessa a verdict was returned on the Jiminez killing from the previous year. Four men were found not guilty of murder. The nineteen-year-old Jiminez, who had moved to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district was gang raped and beaten. Allegedly Jiminez had stolen the shoes of one of the hippies she was living with. As pay-back the people in the apartment – around 10 of them – sexually assaulted her and beat her. She was killed by a kick in the head, her hair cut off and her naked body covered with obscenities scrawled in lipstick. The two cops assigned to the case: Dave Toschi and Bill Armstrong, the two detectives that would later take on Zodiac. No one was charged with murder – it was impossible to determine who made the killing blow, plus no one cared enough. Ann was a fat, lonely, hippie freak, killed by other hippie freaks. This was now a normal thing that happened in San Francisco.

The Ann Jiminez incident was a minor blip during the craziness of 60s America. Both Kennedys were dead, victims of political assassinations. The Vietnam War was still dragging on. Richard Nixon was president, and the governor of California was a Western actor. News of the Manson Murders comes out in the middle of Zodiac’s crime spree. The country was falling apart, as it seems to do so alarmingly often. All of this context is present in Motor Spirt – the book is not just about the Zodiac but about the environment he operated in.

However, aside from the larger picture the book also offers a detailed, accurate account of the whole case. The letters are replicated, the timelines are made clear, the crimes are examined and poured over in meticulous detail. Motor Spirit is the better book of the two – if you read one book about the Zodiac, make it this one. It tells you everything you need to know, and more, without ever being too granular and obsessive. However, How to Find Zodiac is the more interesting read, because there, Kobek presents his theory of the case and he does so incredibly persuasively. The Zodiac is one of us.

How does Kobek find that the Zodiac is one of us? He looks at the source material. The letters. This is how Zodiac wanted to present himself to the public, so that is precisely what Kobek looks at. And he finds a lot. In the Zodiac letters the killer writes that ‘man is the most dangerous animal of all’. Immediately this was taken by the press as a reference to the short story ‘The Most Dangerous Game’ which is about a Russian nobleman becoming so bored that he chooses to hunt people instead of animals. Zodiac also wrote about placing his victims in cages and feeding them salt beef, and then letting them go thirsty. This reference, according to Kobek, is likely to have come from one of two nineteenth century novels that detail the same method of torture. On a creepy Halloween card written to Paul Avery, the San Francisco Chronicle reporter that covered the Zodiac, the killer writes the following: ‘by fire, by gun, by knife, by rope; slaves, paradise’. These ramblings were found to be connected to an old Western comic, Tim Holt #30. On the cover of Tim Holt, the cowboy hero is shown tied up with a roulette wheel behind him showing the ways that he can die: by knife, by rope, by gun, by fire. Kobek sent this piece of information to a friend, an expert on Golden Age comics, who confirmed what Kobek was thinking. Zodiac was a nerd and he probably wrote fanzines. He was one of us.

‘Fanzines were the Internet before the Internet,’ Kobek writes. This is how he found his potential Zodiac. Simply by googling ‘Fanzines Vallejo’ Kobek immediately stumbled upon a pdf of Science Fiction fanzine called Tightbeam. A man named Paul Doerr, who had a Vallejo address, wrote a letter which was, amongst other things, about postal rates and sailing. Doerr wrote about using 1₡ stamps – the Zodiac used six 1₡ for one of his most famous letters. Doerr liked sailing – the Zodiac displayed an intimate knowledge of navigation in one of his letters. Doerr wrote about ‘animals’ and slaves’ in his letters in a similar syntax that the Zodiac did. Doerr was a gun enthusiast, Zodiac clearly was a well. None of this meant for Kobek that Doerr was Zodiac. Instead, he was trying to rule out Doerr as a suspect so he could end an investigation that he didn’t want to start in the first place.

But Kobek couldn’t and still can’t rule Doerr out. After some digging more information is revealed. Doerr was born in 1927 and died in 2007. An army veteran, Doerr moved to California in 1963 to the town of Fairfield, about 20 minutes from Vallejo. He kept a post office box at Vallejo for more than a decade and worked at Mare Island Naval Base. He had a wife and children. Doerr spent his entire life looking for attention, writing letters to the editor in various fanzines and magazines. He never went to college but was an autodidact, and a bit of a maniac as well, having difficulty distinguishing between the science fiction he loved and the reality in which he lived. Doerr believed in Bigfoot, and aliens and other science fiction fads. That doesn’t necessarily make him a murderer though.

Kobek continues his search finding that Doerr had a Lord of the Rings fanzine called Hobbitalia. In it he displays knowledge of codes and ciphers as explains a runic alphabet used by Tolkein’s fictional characters. Also in Hobbitalia Doerr draws diagrams, which look suspiciously similar to Zodiac’s diagrams. Kobek also finds that Doerr was a member of the Society For Creative Anachronism, a group that essentially dresses up in Medieval costumes for fun. This could possibly explain a confusing detail in the Zodiac story. Zodiac, during the Lake Berryesa attack, wore what was described as an executioner’s hood. Doerr may have had one lying around if he enjoyed dressing up in period costumes. Doerr’s world of fanzines is strange but relatable to the readers of Interkom. Doerr was surely weird. He started and read an excessive number of different fanzines (a complete list can be found in the back of the book) but his instinct is one we all share. He wanted to be part of a community of people with similar interests.

What is enjoyable about Kobek’s book is that it is interesting even if Doerr is not the Zodiac. Essentially the book is a biography of someone you have never heard of, and all of the research is done simply by looking at that person’s writing. Kobek has read everything that Doerr wrote that he can get his hands on. He read his crazed letters that he wrote just before his death warning about future pandemics, terrorism, ecological collapse and nuclear war. He read his columns in the American Pigeon Journal. He read his ads in hippie papers seeking girls to come join him on a boat. He read everything, including Doerr confessing to murder in 1974 in a magazine called Green Egg. Using everything he could find Kobek reconstructs the life and thought of man who was deeply strange but also deeply unremarkable.

Throughout the book the evidence against Doerr adds up. Not only is he weird, writing repeatedly throughout the decades about everything from nomadic living; John Norman’s Gor book series that blends Edgar Rice Burroughs-style Science Fantasy adventure with Sado-Masochism and Nietzschean philosophy; comic books and J.R.R. Tolkein to neo-nazism; cave exploration, and female prisoners, Doerr constantly seems to overlap with the Zodiac. He was a member of the radical anti-communist organisation The Minutemen, who have as their symbol a crosshair very similar to the one used by Zodiac. Furthermore, the Minutemen use so-called ANFO bombs, something that was rare at the time and that the Zodiac also mentions in his letters. So there’s the bombs, the letters, the Minutemen, the fact that Doerr lived near Vallejo and collected comic book (before it became a widespread hobby). There’s also Doerr’s knowledge of cryptography, his unhinged nature, his desire for recognition and his long practice of writing to local newspapers in the style of the Zodiac. There’s his murder confessions and, as Kobek reveals right at the end of the book, a photo of Doerr that matches up very closely to the infamous Zodiac sketch. Either Doerr is the Zodiac, or Kobek is totally crazy.

Ultimately it doesn’t matter who the Zodiac is. We’ll never know for sure. Doerr seems as good of a suspect as any, and Kobek makes a thoroughly researched case. Motor Spirit deals with Zodiac by looking at the 60s counterculture as a whole. How to Find Zodiac zooms in instead of out and explores the story of the Zodiac by looking at the fanzine subculture. Kobek writes about the methods that Doerr printed and published his works, how he cultivated a network of readers and respondents, how he was never widely read, but was at least read closely by a few eager fans. All of this is familiar to the readers (and writers) of Interkom. By looking at the Zodiac, Kobek may have finally found him or he may have not. At the very least he’s uncovered a hidden world of science fiction fans, survivalists and far right enthusiasts that is fascinating to explore. Nowadays many of our political pathologies are blamed on the internet. It is no doubt an accelerant, but like-minded people find each other eventually be it through Facebook or through fanzine networks. Doerr might have revealed himself as the Zodiac through his compulsive writing, but he has at the very least revealed himself as one of us. A fan and a fanzine reader.

This article originally appeared in Interkom magazine.