‘Joan Didion didn’t play golf, but her writing had qualities for which all golfers should strive’, so read the headline on the website Golf.com a few days after Didion’s death at the age of eight-seven. They say that all news is local. In that spirit I am going to write that ‘Joan Didion didn’t write science-fiction, but her writing should be of interest to everyone, even science-fiction fans’.

Didion was possibly my favourite writer. Her writing is a perfect combination of form, style and content. She was cold, precise and insightful. She wrote sixteen books, nearly all around 200 pages and most of them non-fiction collections. She jumped around from topic to topic, from American democracy to the nature of grief, yet California remained a through-line of her work. The ‘Golden State’ has been an obsession of mine ever since I studied in Los Angeles for six months. Initially I was put off by the place, but as I grew to understand it, I grew to love it. When I left California, I made sure it did not leave me. I immediately started watching films about it with Inherent Vice, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and Sunset Boulevard being my favourites. I also read California books, starting with Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero, a bleak depiction of teenage life in Reagan-era Los Angeles. Somewhere in an interview, Ellis mentioned that Joan Didion was his biggest inspiration and that he would sit at a typewriter copying out her sentences to see how they worked. So I went out to buy The White Album, Didion’s most famous collection of essays and I was immediately hooked.

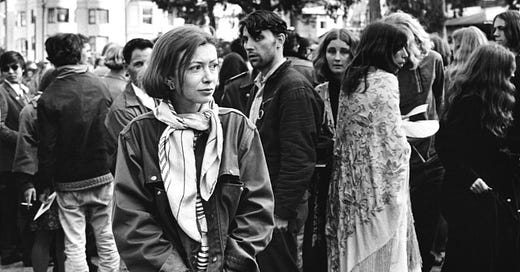

‘We tell ourselves stories in order to live.’ So begins the titular essay of The White Album, which is loosely about the theme of breakdown. Didion sees society breaking down in front of her as the contradictions of 1960s California pile up. She witnesses the rise of the Black Panther Party, the peak of the drug culture, the magnetism of Jim Morrison and the aftermath of the Tate-LaBianca murders. But she also describes her own personal breakdown, excerpting a detailed psychiatric report and noting dryly that ‘an attack of vertigo and nausea does not now seem to me an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968.’ Following the style of ‘The New Journalism’ Didion was placing herself at the heart of the story. Her non-fiction is as much about her reactions and feelings as it is about those of her subjects. She was a quiet observer, but her passivity was so extreme that it turned to aggression. ‘My only advantage as a reporter is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests,’ she wrote in Slouching Towards Bethlehem. She described the world as she saw it and took no prisoners.

Didion was a great writer throughout her life and arguably got even more technically proficient as she aged – the critic John Leonard said of her prose: ‘Try to rearrange one of her sentences, and you’ve realised that the sentence was inevitable, a hologram.’ She wrote a masterpiece, The Year of Magical Thinking, well into her later years, but the real highlight of her career was the trilogy of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Play It As It Lays and The White Album. The two essay collections, and the novel sandwiched between them depict things falling apart. In Slouching Towards Bethlehem Didion wrote about the type of urban decay that is only now beginning to return. The streets of major American cities overrun with crime and homelessness; children taking LSD. In Play It As It Lays her sparse, perfectly constructed Hollywood novel, she looks at the personal impact of 60s individualism and atomisation through the perspective of a failed actress. The White Album considers what happens when we as a society no longer believe the stories we tell ourselves and when reality refuses to correspond to our interpretation.

‘If I was to work again at all, it would be necessary for me to come to terms with disorder,’ Didion wrote, revealing herself ultimately as a conservative writer. Her actual politics were slippery and difficult – she didn’t brag about them every chance she got as is the trend now – but they would certainly shock a large cohort of her fans who venerate as a feminist icon. Photos of her standing in front of Corvette may make for good Instagram posts but they pass over Didion’s conservative outlook. Throughout her 60s and 70s work it is clear that she is on the side of order; the establishment certainly has it issues but it is infinitely preferable to the radicals who destroy nearly everything they touch. Her feminism is also more complex – Didion’s writing on ‘The Women’s Movement’ poked fun at the idea of women as an oppressed class and questioned the claims of the feminist movement, drawing their ire. Finally, her novel, Play It As It Lays shows both the deep physical and moral horror of abortion in her sterile, affectless prose. Didion was too complex to be overly partisan, she began to abandoned the right in the 80s for the same reason she left the left in 60s: a distaste for utopianism and the denial of reality. Yet her outlook, at least compared to her peers, has a distinctive rightward bent. She was formed by the American ideal. Her ancestors buried two children on their way to California in a wagon train. She loved John Wayne. When she was young her grandfather told her to kill a snake if she saw one. These things, above all, formed her politics and her distinct authorial voice.

Joan Didion wasn’t a science-fiction writer by any stretch of the imagination. Try as I might I can’t find any link, however tenuous. But importantly she was a remarkable writer who lived a remarkable life. Her individual sentences fill me with envy with their accomplishment and she used those sentences to describe one of my favourite places in the world. She made California seem like heaven and hell. When I got rejected from university, the first thing I did was find the essay where she wrote about her own experience. It made me feel a whole lot better. Joan Didion didn’t write science-fiction, but her writing should be of interest to everyone, even science-fiction fans.

This article originally appeared in Interkom magazine.